More information for the beginner from writers who have evolved the subject.

As I did research for the “How To Start Backpacking” article, I ran across some great info that I thought needed to be shared. The article was becoming too long so I trimmed it and lost a lot of the detailed information from some very good reading that I think is great info for those starting out. So…

Here is some of that information with links to the wonderful writer’s websites where you can find it in detail.

Summer/Desert Hiking:

Summer's in full

force, and for many of us that means temperatures that belong on a beach, not

in the backcountry. Heading uphill with 40 pounds on your back when the

temperature is climbing into the high 80s or 90s can start to feel like pain,

not pleasure.

Does that mean

you should cancel that long-planned weekend? Or are there ways to overcome the

tyranny of temperature? Read on. . .

First, be

sensible. In general, you don't have to abandon your plans, but if it's 100

degrees and 100-percent humidity, you may seriously wish you had. Consider your

overall fitness level before venturing out in this kind of weather. It can be

dangerous for people with high blood pressure or a heart condition.

Assuming you do

go, pick the place carefully. Exposed rocky ridges might be at higher

elevations (which can mean cooler temperatures), but if the sun is beating down

and the rocks are radiating heat, they may actually be miniature infernos.

Instead, opt for shade and pick a trail that crosses lots of streams—or better

yet, a trail that runs along a stream.

Climb high. Not

to contradict myself, but. . . if you're lucky enough to live near a major

mountain range where you can access trails say four or five thousand feet above

the sweltering lowlands, then by all means, go uphill.

Take plenty of

water. Many hikers find that electrolyte replacement drinks help them replenish

salts and potassium, which are lost when you sweat. Drink them in diluted

quantities of about half strength—they'll do the job and last longer.

Immerse yourself.

Take opportunities to cool down by jumping into whatever body of water is

handy. Periodically dampen a bandanna and wipe your face, neck, and arms.

Go easy on the

mileage and don't plan huge elevation gains.

Bring some sort

of treatment for blisters. Heat causes feet to swell, and sweat, both of which

contribute to blistering.

Wear clothing

that wicks sweat from your skin—a polyester T-shirt, not cotton.

>>

Basics from Backpacker Magazine website – “How

To Do Everything”:

STAY

DRY IN A DOWNPOUR

- Make sure the cuffs of your baselayer aren't exposed, or they'll wick moisture up your sleeves.

- Keep your jacket hem cinched snugly and shield your face by pulling your hood over a billed cap.

- In wet brush, wear rain pants over gaiters. Use trash bags as makeshift gaiters.

- Don't get wet from the inside out. If you're overheating, minimize sweat by shedding layers or slowing your pace.

NAVIGATE

OFF-TRAIL

Step 1: Adjust for declination

Declination is simply the difference between magnetic north (where the compass needle points) and true north (the North Pole, and the direction maps are oriented). To navigate accurately, just check the margin of your map for the declination (12 degrees east, for instance) and adjust your compass accordingly (most have a simple dial). No dial? No problem. If the declination is east, subtract the degrees from the magnetic north bearing to get the true bearing; if it's west, add the degrees (easy mnemonic device: East is least, west is best).

Step 1: Adjust for declination

Declination is simply the difference between magnetic north (where the compass needle points) and true north (the North Pole, and the direction maps are oriented). To navigate accurately, just check the margin of your map for the declination (12 degrees east, for instance) and adjust your compass accordingly (most have a simple dial). No dial? No problem. If the declination is east, subtract the degrees from the magnetic north bearing to get the true bearing; if it's west, add the degrees (easy mnemonic device: East is least, west is best).

Step 2: Orient

your map

Lay the straight edge of your compass on the map so that its true north bearing is parallel to the map's true north grid lines. Rotate the map and compass together until the compass points due north.

Lay the straight edge of your compass on the map so that its true north bearing is parallel to the map's true north grid lines. Rotate the map and compass together until the compass points due north.

Step 3: Take a

bearing

Let's say your destination is a spectacular lakeside campsite two miles off the beaten path. You can see it on your map–but not from the trail. To get there, lay the straight edge of your compass base plate on the map so it connects your present location with the lake. Turn the compass housing until its meridian lines match the north-south lines on the map (make sure the arrow is pointing to the top of the map, or you'll be 180 degrees off). The direction indicated at the compass's direction of travel arrow is the route you need to take to reach the lake.

Let's say your destination is a spectacular lakeside campsite two miles off the beaten path. You can see it on your map–but not from the trail. To get there, lay the straight edge of your compass base plate on the map so it connects your present location with the lake. Turn the compass housing until its meridian lines match the north-south lines on the map (make sure the arrow is pointing to the top of the map, or you'll be 180 degrees off). The direction indicated at the compass's direction of travel arrow is the route you need to take to reach the lake.

Step 4: Navigate

around obstacles

In the real world, obstacles like canyons and cliffs can get in the way of your straight line bearing. Here's how to go around without getting off track: With your compass in hand, sight an object–like a tree or boulder–that is beyond the obstacle and lies on the straight line to your destination. Hike to that object by the easiest route, then resume traveling along your original bearing.

In the real world, obstacles like canyons and cliffs can get in the way of your straight line bearing. Here's how to go around without getting off track: With your compass in hand, sight an object–like a tree or boulder–that is beyond the obstacle and lies on the straight line to your destination. Hike to that object by the easiest route, then resume traveling along your original bearing.

1) Sun Hold an analog watch flat, with the hour hand pointing to the sun. South is halfway between the hour hand and 12.

2) Shadows Stand a 3-foot stick vertically in the ground and mark the tip of its shadow with a rock. Wait at least 15 minutes, then mark the shadow again. The line connecting the two roughly coincides with the east-west line.

3) Stars Find the Big Dipper. Follow an imaginary line drawn through the two stars at the end of the cup and extending into the sky to a medium-bright star–this is Polaris, the North Star.

4) Moon Watch the sky. If the crescent moon rises before sunset, its illuminated side will face west. If it rises after midnight, the brighter side faces east.

5) Plants In Eastern and Midwestern prairies, find the bright-yellow bloom of a compass plant (Silphium laciniatum, right). In sunny spots, its leaves generally align themselves along the north-south line.

BEAT FATIGUE ON STEEP CLIMBS

When high altitude and big mountains take their toll, use the "rest step." With each stride, lock your downhill knee, shifting the weight momentarily onto that back leg. This puts your weight on your bones for a moment, allowing your leg muscles to relax. As you take your next step, transfer your weight to the uphill leg and let momentum swing your downhill foot forward. Repeat. Inhale deeply as you step up; exhale deeply as you pause in the rest step. If you're feeling especially winded, try "pressure breathing": Exhale forcefully through pursed lips as if you're blowing out a candle to push oxygen from the alveoli to the bloodstream.

When high altitude and big mountains take their toll, use the "rest step." With each stride, lock your downhill knee, shifting the weight momentarily onto that back leg. This puts your weight on your bones for a moment, allowing your leg muscles to relax. As you take your next step, transfer your weight to the uphill leg and let momentum swing your downhill foot forward. Repeat. Inhale deeply as you step up; exhale deeply as you pause in the rest step. If you're feeling especially winded, try "pressure breathing": Exhale forcefully through pursed lips as if you're blowing out a candle to push oxygen from the alveoli to the bloodstream.

4 WAYS TO PREVENT BLISTERS

1) Buy shoes that allow room for your feet to swell. Break them in by wearing them around town and on dayhikes.

2) Wear wicking socks (synthetic or wool); change into a fresh pair as needed. Hang on your pack to dry.

3) Reduce friction by smearing trouble areas with Sportslick or Bodyglide.

4) Stop and cover hotspots immediately with moleskin, Adventure Medical Kits GlacierGel pads, or plain old duct tape.

1) Buy shoes that allow room for your feet to swell. Break them in by wearing them around town and on dayhikes.

2) Wear wicking socks (synthetic or wool); change into a fresh pair as needed. Hang on your pack to dry.

3) Reduce friction by smearing trouble areas with Sportslick or Bodyglide.

4) Stop and cover hotspots immediately with moleskin, Adventure Medical Kits GlacierGel pads, or plain old duct tape.

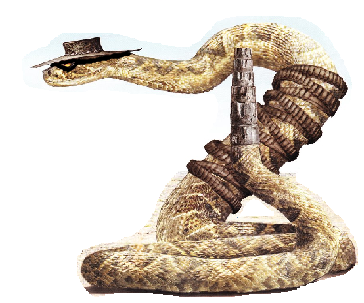

READ

A RATTLESNAKE'S BODY LANGUAGE

|

| If it looks like a gunslinger out for blood, it probably is. |

- Coiled, with tail parallel to ground: All clear–it's just hanging out

- Coiled, with tail in the air: On the prowl, looking for mice

- Rattle up, head and upper body raised off the ground: Ready to strike. Slowly back away!

>>

One of THE BEST articles for “How To Backpack”

Stuff:

WATER

From a purely

weight-centric perspective, the overriding question a hiker needs to ask in

regards to water is: How can I minimize the amount I am carrying, without

running the risk of becoming dehydrated? Consider the following six

points.

1. Do your

Homework - Before setting

out on a hike, always know where your water will be coming from. Knowing the

location, current status and quality of your water sources allows you to plan

in advance, thereby minimizing the need to carry large quantities of extra

water for insurance purposes.

2. Morning

Investment - Before breaking

camp, make a habit of drinking one litre of water (when you are near a water

source). Think of it as a “hydration” investment for the rest of the day. The

more you drink early, the less you will need to drink (and carry) later on.

3. ‘Camel Up’

- If you are hiking

in terrain where opportunities to fill your bottles are few and far between,

drink at least one litre of water before leaving each source. By doing so

you will not need to carry as much to the next refill point, which in turn

translates to less weight on your back and more spring in your step.

4. Timing - In hot, largely shadeless (unshaded)

conditions where water sources are scarce, do the bulk of your hiking whilst

temperatures are cooler (i.e. early morning, late afternoon and early

evening). By following such a strategy, it is possible to make do with

less water because you are resting rather than exerting during the hottest part

of the day.

5. Cooking

- In arid

environments, plan to eat your main meals at water sources, thus negating the

need to carry extra water for cooking purposes.

Human Waste Disposal

in the Backcountry: How to pee and poop in the woods

Most hikers, backpackers, and climbers know that answering the call of

nature in the backcountry can present an interesting (sometimes embarrassing)

challenge. At the very least, it may cause uncertainty. What are the rules?

When and where is it okay to dig? What's this “blue bag” business?

As a growing number of outdoors people head into the backcountry

pondering those questions, the impacts on the landscape are growing, too. Some

suggested practices are changing as human waste disposal in the great outdoors

continues to have serious environmental, health, and aesthetic impacts.

Here, for all of you who've pondered “dig or pack it out?” when rules are

unclear, wished for a Port-o-Biff at 12,000 feet, or have worries about using a

WAG Bag, are guidelines for taking care of business in an earth-friendly way

when you're miles from indoor plumbing.

This article has some good specifics and cover a lot about such an

intimate subject.

Like: “First, a Word About Number One”

“Dig or bury”

And

“For Women Only - Pee Positions”

You just don’t get that kind of in-depth reading many places.

Oh, and…

Pack-Out

Musts

Some waste items

you always pack out, no matter where you are, what the climate, is or how small

an item it is. Those items include tampons, pads, and other feminine hygiene

products (see the Women Only section belowand diapers.

More on “Going”:

>>

Even More on the psychology of backpacking:

Boredom

and Loneliness

"How could someone be bored when fighting for his or her life?" you might ask.

"How could someone be bored when fighting for his or her life?" you might ask.

Quite easily,

actually. When boredom is experienced it is a sign that the survivor is not

grasping the seriousness of the situation, and therefore is not going about the

business of systematic survival. It can also be a sign of a lack of the most

powerful survival tool—the will to live. People unfamiliar with nature tend to

become bored faster than those who have a practical understanding of the

environment they are in. Those who know the woods, swamp, mountains, or desert

that they are "stranded" in tend to pick up on important, beneficial

information faster than those who feel intimidated or otherwise uncomfortable

in their surroundings.

Loneliness is

very common. Man is by nature a social animal—we crave human companionship.

When you feel lonely you may become forlorn, which can lead to a feeling of

helplessness. Just because you are alone doesn't mean you must be lonely.

The key to

dealing with both of these threats is useful activity. The busier you are, the

less bored and lonely you will feel. When you think that nothing else can be

done to increase the chances of your getting out alive, reevaluate and think

again. There is always something practical to be done when trying to survive.

Always.

Pain

We know that pain is your body telling your brain that something is amiss. Most would-be survivors that are in pain go wrong by ignoring or incorrectly assessing the gravity of the wound or ailment.

We know that pain is your body telling your brain that something is amiss. Most would-be survivors that are in pain go wrong by ignoring or incorrectly assessing the gravity of the wound or ailment.

Every one of us

has applied basic first-aid, like washing a shallow knife wound or applying a

bag of ice to a twisted ankle. We think nothing of these injuries and deal with

them almost without thinking—they are routine. But when stuck on an uninhabited

island in the Gulf of Maine because your kayak and camping gear went out to sea

without you when the tide came in, a cut or twisted ankle becomes more serious.

Now that seemingly insignificant wound means reduced manual dexterity and/or

restricted movement, making gathering material to make a fire, getting water,

or erecting a shelter much more difficult.

Minor wounds and

maladies have a way of quickly becoming serious in survival situations. You

must never assume anything when it comes to medical problems, regardless of how

little it hurts or how petty the problem appears at first.

Thirst

Many people fail to realize that our bodies use water as a coolant all the time, not just during warm weather. At the Navy Survival School where I used to teach wilderness survival techniques, dehydration was the most common malady experienced. It can creep up on you without you ever really knowing that it is there. Symptoms include a nasty headache, unusual fatigue, dark urine, irritability, and dizziness.

Many people fail to realize that our bodies use water as a coolant all the time, not just during warm weather. At the Navy Survival School where I used to teach wilderness survival techniques, dehydration was the most common malady experienced. It can creep up on you without you ever really knowing that it is there. Symptoms include a nasty headache, unusual fatigue, dark urine, irritability, and dizziness.

Even a seemingly

minor fluid loss, say, 2 percent or so, results in pale, clammy skin, nausea,

general discomfort, a lack of cooperation, a demonstrated lack of physical

strength, elevated heart rate, sleepiness, and decreased appetite. The key to

fluid replacement is quite simple: drink water, and plenty of it. Sports drinks

such as Gatorade are fine for the replacement of electrolytes, but should be

diluted to reduce the sugar level so that the body can easily absorb the water

from the stomach—sugar slows down the absorption rate.

Fatigue

Fatigue is one of the most preventable threats to your survival. When not recognized and dealt with it can be fatal. A tired survivor swinging a hatchet to chop some firewood is more likely to injure himself than the survivor who is well rested. The exhausted survivor can not cope with the other six threats as readily as he who has been taking short "cat" naps and getting the right amount of sleep at night.

Fatigue is one of the most preventable threats to your survival. When not recognized and dealt with it can be fatal. A tired survivor swinging a hatchet to chop some firewood is more likely to injure himself than the survivor who is well rested. The exhausted survivor can not cope with the other six threats as readily as he who has been taking short "cat" naps and getting the right amount of sleep at night.

What is the right

amount of sleep? Simply, the right amount of sleep is dictated by the body—when

you awaken and feel rested, you have had the right amount of sleep. Even a

couple of hours of missing sleep can adversely effect your work output and

ability to make sound decisions when needed. To facilitate sleep you must tend

to the chores that will make your survival episode more palatable. You just

can't expect to get plenty of sleep if you are freezing because your fire and

shelter-building skills were not up to speed. Everything in your survival plan

is interrelated.

Your physical

condition is very likely to be the best it is going to be as you enter your

survival episode. In other words, as time drags on your physical (and mental)

condition is likely to deteriorate because of your imperfect handling of one or

more of these seven threats. A slip of the knife that makes a deep cut in your

finger makes camp chores more difficult. You forgot or didn't bother to purify

the water you drank in that stream, and now your insides are raising a ruckus.

Your signal plan wasn't ready for that search plane when it went right over

you, and now you are terribly depressed and feeling like all is lost and

hopeless. You don't dare eat any of the dozens of edible plants you passed

today because you didn't know which were edible and which weren't—now you

haven't had any food in four days, you feel weak, and your strength is waning.

Temperature

Extremes

Regardless of where you think humankind hails from, one fact remains undeniable: man is a tropical animal. This means that he can't survive naked year-round unless he is in the tropics.

Regardless of where you think humankind hails from, one fact remains undeniable: man is a tropical animal. This means that he can't survive naked year-round unless he is in the tropics.

Given this, the

survivor must take temperature extremes very seriously. Not only the cold, mind

you, but the heat as well. Add to that wind, humidity, and precipitation. In

other words every facet of the weather has to be carefully considered in your

survival plan. The part you forget will be the part that comes back to bite

you.

Underestimating

the weather will get you dead in a hurry. Even seemingly mild temperatures can

and have become fatal for survivors who failed to take precautions. A moderate

rain in 40-degree weather can quickly become life threatening to the man or

woman who is soaked. Hypothermia (a sustained cooling of the body's core

temperature) and heat illness (where the body's core temperature raises to and

stays above 100 degrees Fahrenheit) are two of the most common problems

experienced by survivors, and they are preventable in nearly all circumstances.

Underestimating

the weather will get you dead in a hurry. Even seemingly mild temperatures can

and have become fatal for survivors who failed to take precautions. A moderate

rain in 40-degree weather can quickly become life threatening to the man or

woman who is soaked. Hypothermia (a sustained cooling of the body's core

temperature) and heat illness (where the body's core temperature raises to and

stays above 100 degrees Fahrenheit) are two of the most common problems

experienced by survivors, and they are preventable in nearly all circumstances.

Symptoms of

hypothermia include uncontrollable shivering, slowed reactions, weak motor

skills, lethargy, reduced ability to make decisions, irritability, and speech

that has become slurred and possibly incomprehensible.

Symptoms of heat

illness are wide ranging, too, and depend on the degree of the illness. Heat

exhaustion is recognized by dizziness, thirst, physical weakness, possible

nausea, a nasty headache, and a body temperature between 102 and 104 degrees

Fahrenheit. This can be seen prior to heat stroke, but not always. Heat stroke,

which effects the brain, is more serious than heat exhaustion. The pulse and

respiration increases, delirium is common, and the body temperature shoots to

over 104 degrees Fahrenheit. The victim may even become comatose.

The answer to

both of these heat-related problems is to quickly cool the body with water and

fanning; give water if the patient is conscious; and once the body temperature

is back down, keep it that way.

Hunger

It's no secret that the human body can go without food much longer than it can without water. Still, food is important to the five-day survivor insofar as work output, morale, and decision-making are concerned.

It's no secret that the human body can go without food much longer than it can without water. Still, food is important to the five-day survivor insofar as work output, morale, and decision-making are concerned.

Your survival

plan should not revolve around acquiring food. Rather, it should be focused on

signals, water, shelter, fire, and if necessary, first aid. Food is too easy to

come by to devote a great deal of time searching for and preparing.

The key to

getting fed while surviving lies not in fashioning marvelously complex snares

and traps to catch game, but in foraging for simply found and collected edibles

such as plants, fish, and certain amphibians. These three types of food are the

easiest things to come by and prepare for breakfast, lunch, or dinner. All the

survivor has to do is have a basic understanding of what plants in the area are

edible, where they are likely to be located, and what they look like; what fish

live where and what they eat; and how to catch frogs and other amphibians.

The key to

getting fed while surviving lies not in fashioning marvelously complex snares

and traps to catch game, but in foraging for simply found and collected edibles

such as plants, fish, and certain amphibians. These three types of food are the

easiest things to come by and prepare for breakfast, lunch, or dinner. All the

survivor has to do is have a basic understanding of what plants in the area are

edible, where they are likely to be located, and what they look like; what fish

live where and what they eat; and how to catch frogs and other amphibians.

Remember that the

amount of energy you expend foraging for food must never exceed the number of

calories and general value you will glean from that food. You have to get more

than you give. If you use a thousand calories chasing leopard frogs all

afternoon and only catch one, you are losing the battle.

It is much

smarter to collect edible plants and slower frogs while gathering firewood for

the evening and for your signal fires than it is chasing rabbits through the

brush with a stick. And if you set out some limb lines before you go

a-gathering, you will probably have some fish to eat when you get back to camp.

Fear

Although you have no doubt read of the dramatic rise in mountain lion attacks on man in southern California or of alligators eating people down South, the chances of becoming the victim of such an animal is extremely remote—almost too remote to even give a single thought to. You stand a much better chance of being stung by yellowjackets or poked with the sharp dorsal spine of a bluegill than being eaten or torn up by a bear, 'gator, or cougar. But survivors fear much more than wild animals.

Although you have no doubt read of the dramatic rise in mountain lion attacks on man in southern California or of alligators eating people down South, the chances of becoming the victim of such an animal is extremely remote—almost too remote to even give a single thought to. You stand a much better chance of being stung by yellowjackets or poked with the sharp dorsal spine of a bluegill than being eaten or torn up by a bear, 'gator, or cougar. But survivors fear much more than wild animals.

Fear of the

unknown—the future and whether or not you have one—is the primary fear

experienced by survivors. You just don't know for sure if you are going to be

rescued or if you are going to find a way out of the mess you have gotten

yourself into. This fear, which is experienced to one degree or another by all

survivors regardless of the level of training or life experiences they may

have, can be just as much a healthy thing as a debilitating one. Fear has a way

of forcing you to act, and action is what survival is all about. This action

includes building a quick and worthy shelter, starting and maintaining a fire

in the rain, finding and preparing plants and fish for supper, fixing yourself

when you are injured or sick, getting water, and setting up a signal system.

Then your fears will turn from the grim—ending up dead—to the vain worries

about what clever quip you are going to whip on your rescuers when they finally

show up—so that the newspaper articles and television reports about your little

problem don't make you out for a complete fool.

Read more: http://www.gorp.com/hiking-guide/travel-ta-hiking-hunting-sidwcmdev_056153.html#ixzz367aJ8NLK

Have fun and stay safe.

Now go outside and play/

Johnny